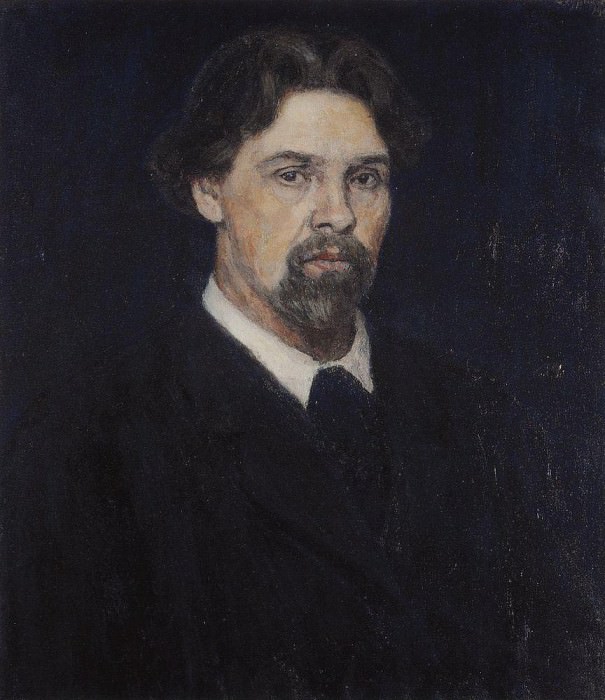

Self-portrait Vasily Ivanovich Surikov (1848-1916)

Vasily Ivanovich Surikov – Self-portrait

Edit attribution

Download full size: 864×1000 px (0,1 Mb)

Painter: Vasily Ivanovich Surikov

Surikov’s oeuvre is loved by us primarily for his historical canvases. "The Morning of the Streletsky Execution," "The Seizure of Siberia by Yermak," "Boyarynya Morozova" - these and other paintings by Surikov are known to everyone. But his portrait work is no less interesting, especially the paintings that depict the artist himself. In all his time he created about fifteen self-portraits, giving the opportunity to see Surikov in different years of life. "Self-Portrait" (1913), which is now a valuable exhibit at the Tretyakov Gallery, is rightly considered the pinnacle of Surikov’s late work.

Description of Vasily Surikov’s painting Self-Portrait

Surikov’s oeuvre is loved by us primarily for his historical canvases. "The Morning of the Streletsky Execution," "The Seizure of Siberia by Yermak," "Boyarynya Morozova" - these and other paintings by Surikov are known to everyone. But his portrait work is no less interesting, especially the paintings that depict the artist himself. In all his time he created about fifteen self-portraits, giving the opportunity to see Surikov in different years of life.

"Self-Portrait" (1913), which is now a valuable exhibit at the Tretyakov Gallery, is rightly considered the pinnacle of Surikov’s late work. Painted three years before his death, the canvas depicts a moment of crisis for the artist, when the rise of talent was left far behind.

The painting stands out for its compositional laconism that is common for all portraits of this period. The particular effect of the depicted figure merging with the background proves that at the beginning of the century Surikov took into consideration the artistic principles of his contemporary movements. Dark, muted tones are intended to convey a sense of deep hidden and outwardly not manifested in any way drama. Such was the artist and in life: verbose, closed to outsiders.

Meanwhile, we can not say that the depicted figure expresses despair or sadness. On the contrary, a man, full of inner strength, looks at us attentively, a little sternly. And you can’t tell that the artist (or Cossack?) is sixty-five years old and has experienced a lot of hardship.

Perhaps, for someone in this portrayal will come through Surikov’s earlier works, depicting folk heroes such as Suvorov or Ermak. Such an interpretation would certainly appeal to the artist himself, who, as can be seen in his self-portrait made in 1902, emphasized in every possible way that among his ancestors were Cossacks, strong, daring people.

Кому понравилось

Пожалуйста, подождите

На эту операцию может потребоваться несколько секунд.

Информация появится в новом окне,

если открытие новых окон не запрещено в настройках вашего браузера.

You need to login

Для работы с коллекциями – пожалуйста, войдите в аккаунт (open in new window).

You cannot comment Why?

The man’s face displays a complex interplay of expression. While theres an element of stoicism in his posture and gaze, subtle nuances suggest introspection and perhaps even melancholy. The lines around his eyes and mouth hint at experience and a certain weariness. A full beard, neatly trimmed but retaining a degree of wildness, frames the lower portion of his face, contributing to a sense of gravitas and intellectual depth.

The artist employed a loose, expressive brushstroke throughout the work. This technique is particularly evident in the rendering of the hair, which appears voluminous and textured, with individual strands suggested rather than precisely defined. The clothing – a dark jacket over a crisp white shirt and tie – is rendered with similar fluidity, avoiding sharp outlines and contributing to the overall impression of immediacy and spontaneity.

The lighting is carefully orchestrated; it illuminates the face from an unseen source, creating highlights on the forehead, nose, and chin while leaving areas in shadow, which enhances the three-dimensionality of the figure and adds depth to his expression. The contrast between light and dark contributes to a dramatic effect, further emphasizing the subject’s presence.

Subtly, there is a sense of vulnerability conveyed through the direct gaze and the slightly downturned mouth. It suggests an individual who is both self-assured and burdened by internal thoughts or experiences. The lack of background detail encourages viewers to project their own interpretations onto the figure, fostering a connection that transcends mere representation. The overall effect is one of quiet dignity and profound introspection.